A

VIRGINIA GIRL IN THE FIRST YEAR OF THE WAR

by C. C. Harrison .As

Published in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. XXX;

New Series Vol. VIII, May 1885, to October 1885; The Century CO, New York;

F. Warne & Co., London.

Note:

To the best of my knowledge, this material has not been republished since

its original appearance in 1885, and as such resides in the public domain.

Interested readers are invited to save the file for personal use only.

Please

allow extra time for graphics to load.

The Beginning -

The only association I

have with my old home in Virginia, that is not one of unmixed happiness,

relates to the time immediately succeeding the execution of John brown

at Harper's Ferry. Our homestead was in Fairfax, at a considerable distance

from the theater of that tragic episode; and, belonging as we did to a

family among the first in the State to manumit slaves - our grandfather

having set free those which came to him by inheritance, and the people

who served us being hired from their owners and remaining in our employ

through years of kindliest relations - there seemed to be no especial reason

for us to share in the apprehension of an uprising by the blacks. But there

was the fear - unspoken, or pooh-poohed at by the men who served as mouth-pieces

for our community - dark, boding, oppressive, and altogether hateful. I

can remember taking it to bed with me at night, and awaking suddenly oftentimes

to confront it through a vigil of nervous terror of which it never occurred

to me to speak to any one. The notes of whip-poor-wills in the sweet-gun

swamp near the stable, the mutterings of a distance thunder-storm, even

the rustle of the night wind in the oaks that shaded my window, filled

me with nameless dread. In the day-time it seemed impossible to associate

suspicion with those familiar tawny or sable faces that surrounded us.

We had seen them for so many years smiling or saddening with the family

joys or sorrows; they were so guileless, so patient, so satisfied. What

subtle influence was at work that should transform them into tigers thirsting

for our blood? The idea was preposterous. But when evening came again,

and with it the hour when the colored people (who in summer and autumn

weather kept astir half the night) assembled themselves together for dance

or prayer-meeting, the ghost that refused to be laid was again at one's

elbow. Rusty bolts were drawn and never before had eye or ear been lent

to such a service. Peace, in short, had flown from the borders of Virginia.

I cannot remember that,

as late as Christmas-time of the year 1860, although the newspapers were

full of succession talk and the matter was eagerly discussed at our tables,

coming events had cast any positive shadow on our homes. The people in

our neighborhood, of one opinion with their dear and honored friend, Colonel

Robert E. Lee, of Arlington, were slow to accept the startling suggestion

of disruption of the Union. At any rate, we enjoyed the usual holiday gathering

of kinsfolk in the usual fashion. The old Vaucluse house, known for many

years past as the center of cheerful hospitality in the country, threw

wide open its doors to receive all the members who could be gathered there

of a large family circle. The woods around were despoiled of holly and

spruce, pine and cedar, to deck the walls and wreathe the picture-frames.

On Christmas Eve we had a grand rally of youths and boys belonging to the

"clan," as they loved to call it, to roll in a Yule log, which was deposited

upon a glowing bed of coals in the big "red parlor" fire-place, and sit

around it afterwards, welcoming the Christmas in with goblets of eggnog

and apple-toddy.

"Where shall we be a year

hence?" someone asked at a pause in the merry chat; and in the brief silence

that followed, arose a sudden spectral thought of war. All felt its presence;

no one cared to speak first of the grim possibilities it projected on the

canvas of the future.

On Christmas Eve of the

following year the old house lay in ruins, a sacrifice to military necessity;

the forest giants that kept watch around her walls has been cut down and

made to serve as breastworks for a fort erected on the Vaucluse property,

but afterwards abandoned. Of the young men and boys who took part in that

holiday festivity, all were in active service of the South, - one of the,

alas! soon to fall under a rain of shot and shell beside his gun at Fredericksburg;

the youngest of the number had left his mother's knee to fight in the battles

of Manassas, and found himself, before the year was out, a midshipman aboard

the Confederate steamer Nashville, on her cruise in distant seas!

My first vivid impression

of war-days was during a ramble in the woods around our place one Sunday

afternoon in spring, when the young people in a happy band set out in search

of wild flowers. Pink honeysuckle's, blue lupine, beds of fairy flax, anemones,

and firs in abundance sprung under the canopy of young leaves on the forest

boughs, and the air was full of the song of birds and the music of running

waters. We knew every mossy path far and near in these woods, y every tree

had been watched and cherished by those who went before us, and dearer

than any other spot on earth was our tranquil, sweep Vaucluse. Suddenly

the shrill whistle of a locomotive struck the year, an unwonted sound on

Sunday. "Do you know what that means"? said one of the older cousins who

accompanied the party. "It is the special train carrying Alexandria volunteers

to Manassas, and to-morrow I shall follow with my company." An awe-struck

silence fell upon our little band. A cloud seemed to come between us and

the sun. It was the beginning of the end too soon to come.

The story of one broken

circle is the story of another at the outset of such a war. Before

the week was over, the scattering of our household, which no one then believed

to be more than temporary, had begun. Living as we did upon ground likely

to be in the track of armies gathering to confront each other, it was deemed

advisable to send the children and young girls into a place more remote

from chances of danger. Some weeks later the heads of the household,

two widowed sisters, whose sons were at Manassas, drove in their carriage

at early morning, away from their home, having spent the previous night

in company with a half-grown lad digging in the cellar hasty graves for

the interment of two boxes of old English silver-ware, heirlooms in the

family, for which there was no time to provide otherwise. Although troops

were long encamped immediately above it after the house was burnt the following

year, this silver was found when the war had ended, lying loose n the earth,

the boxes having rotted from around it.

Bristoe -

The point at which our

family reunited within Confederate lines was Bristoe, the station next

beyond Manassas, a cheerless railway inn; a part of the premises was used

as a country grocery; and the quarters were secured for us with a view

to being near the army, a few miles distant. By this time all our kith

and kin of fighting age had joined the volunteers. One cannot picture accommodations

more forlorn than these eagerly taken for us and for other families attracted

to Bristoe by the same powerful magnet. The summer sun poured its burning

rays upon whitewashed walls unshaded by a tree. Our bedrooms were almost

uninhabitable by day or night, our far the plainest. From the windows we

beheld only a flat, uncultivated country, crossed by red-clay roads, then

knee-keep in dust. We learned to look for all excitement to the glittering

lines of railway track, along which continually thundered trains bound

to and from the front. It was impossible to allow such a train to pass

without running out upon the platform to salute it, for in this way we

greeted many an old friend or relative buttoned up in the smart gray uniform,

speeding with high hope to the seen of coming conflict. Such shouts was

went up from sturdy throats when the locomotive moved on after the last

stop before Manassas, while we stood waving hands, handkerchiefs, or the

rough woolen garments we were at work upon! Then fairly awoke the spirit

that made of Southern women the inspiration of Southern men for the war.

Most of the young fellows we were cheering onward wore the uniform of privates,

and for the right to wear it had left homes of ease and luxury. To such

we gave our best homage; and from that time forth, during the four years

succeeding, the youth who was lukewarm in the cause of unambitious of military

glory fared uncomfortably in the presence of the average Confederate maiden.

Thanks to our own carriage,

we were able during those rallying days of June to drive frequently to

visit our boys in camp, timing the expeditions to include battalion drill

and dress parade, and taking tea afterwards in the different tents. Then

were the gala days of war, and our proud hosts hastened to produce home

dainties dispatched from the far-away plantations - tears and blessings

interspersed amid the packing, we were sure; though I have seen a pretty

girl persist in declining other fare, to make her meal upon raw biscuit

and huckleberry pie compounded by the bright-eyed amateur cook of a well-beloved

mess. Feminine heroism could no farther go.

Charge of Confederates

Upon Randol's Battery at Frayser's Farm

During the Seven Days

Fighting about Richmond.

(Drawn by A. C. Redwood)

And so the days wore on

until the 17th of July, when a rumor from the front sent an electric shock

through our circle. The enemy were moving forward! On the morning of the

18th those who had been able to sleep at all awoke early to listen for

the first guns of the engagement of Blackburn's Ford. Abandoned as the

women at Bristoe were by every masculine creature old enough to gather

news, there was, for them, no way of knowing the progress of events during

the long, long day of waiting, of watching, of weeping, of praying, of

rushing out upon the railway track to walk as far as they dared in the

direction whence came that intolerable booming of artillery. The cloud

of dun smoke arising over Manassas became heavier in volume as the day

progressed. Still, not a word of tidings, till toward afternoon there

came limping by a single, very dirty soldier with his arm in a sling. What

a heaven send he was, if only as an escape-valve for our pent-up sympathies!

We seized him, we washed him, we cried over him, we glorified him until

the man was fairly bewildered. Our best endeavors could only develop a

pin-scratch of a wound on his right hand; but when our hero had laid in

a substantial meal of bread and meat, we plied him with trembling questions,

each asking news of some staff or regiment or company. It has since occurred

to me that this first arrival from the field was a humorist in disguise.

His invariable reply, as he looked from one to the other of his satellites,

was: "The _ Virginia, marm? Why, of coase. They warn't no two ways o' thnkin'

'bout that ar rig'ment. They just kivered tharselves with glory!"

A little later two wagon-loads

of slightly wounded claimed our care, and with them came authentic news

of the day. Most of us received notes on paper torn from a soldier's pocket-book

and grimed with gunpowder, containing assurance of the safety of our own.

At nightfall a train carrying more wounded to the hospitals at Culpeper

made a halt at Bristoe; and, preceded by men holding lanterns, we went

in among the stretchers with milk, food, and water to the suffers.

One of the first discoveries I made, bending over in that fitful light,

was a young officer I knew to be a special object of solicitude with one

of my fair comrades in the search; but he was badly hurt, and neither he

nor she knew the other was near until the train had moved on. The next

day, and the next, were full of burning excitement over the impending general

engagement, which people then said would decide the fate of the young Confederacy.

Fresh troops came by with every train, and we lived only to turn from one

scene to another of welcome and farewell. On Saturday evening arrived a

message from General Beauregard, saying that early n Sunday an engine and

car would be put at our disposal, to take us to some point more remote

from danger. We looked at one another, and, tacitly agreeing that the gallant

general had sent not an order, but a suggestion, declined his kind proposal.

Another unspeakably long

day, full of the straining anguish of suspense. Dawning bright and fair,

it closed under a sky darkened by cannon-smoke. The roar of guns seemed

never to cease. First, a long sullen boom; then a sharper rattling fire,

painfully distinct; then stragglers from the field, with varying rumors.

At last, the news of victory; and, as before, the wounded, to force our

numbed faculties into service. One of our group, the mother of an only

son barely fifteen years o age, heard that her boy, after being in action

all the early part of the day, had through sheer fatigue fallen sleep upon

the ground, where his officers had found him, resting peacefully amidst

the roar of the guns, and whence they had brought him off, unharmed. A

few days later we rode on horseback over the field of the momentous fight.

The trampled grass had begun to spring again, and wild flowers were blooming

around carelessly made graves. From one of these imperfect mounds of clay

I saw a hand extended; and when, years afterwards, I visit the tomb of

Rousseau beneath the Pantheon in Paris, where a sculptured hand bearing

a torch protrudes from the sarcophagus, I thought of the mournful spectacle

upon the field of Manassas. Fences were everywhere throw down; the undergrowth

of the woods was riddled with shot; here and there we came upon spiked

guns, disabled gun-carriages, cannon-balls, blood-stained blankets, and

dead horses. We were glad enough to turn away and gallop homeward.

Culpeper -

With August heats and

lack of water, Bristoe was forsaken for quarters near Culpeper, where my

mother went into the soldiers' barracks, sharing soldiers' accommodations,

to nurse the wounded. In September quite a party of us, upon invitation,

visited the different headquarters. We stopped overnight at Manassas, five

ladies, sleeping in a tent guarded by a faithful sentry, upon a couch made

of rolls of cartridge-flannel. I remember the comical effect of the five

bird-cages (as article without which no self-respecting female of that

day would present herself in public) suspended upon a line running across

the upper part of our tent, after we had reluctantly removed them in order

to adjust ourselves for repose. Our progress during that memorable visit

was royal; an ambulance with a picked troop of cavalrymen had been placed

at our service, and the convoy was "personally conducted" by a pleasing

variety of distinguished officers. It was at this time, after a supper

at the headquarters of the "Maryland line" at Fairfax, that the afterwards

universal war-song "My Maryland," was set afloat upon the tide of army

favor. We were sitting outside a tent in the warm starlight of an early

autumn night, when music was proposed. At once we struck up Randall's verses

to the turn of the old college song, "Lauriger Horatius," - a young lady

of the party from Maryland, a cousin of ours, having recently set them

to this music before leaving home to share the fortunes of the Confederacy.

All joined in the ringing chorus, and when we finished a burst of applause

came from some soldiers listening in the darkness behind a belt of trees.

Next day the melody was hummed far and near through the camps, and in due

time it had gained and held the place of a favorite song in the army. No

doubt the hand-organs would have gotten hold of it; but, from first to

last during the continuance of the Confederacy, those cheerful instruments

of torture were missing. (I hesitate to mention this fact, lest it prove

an incentive to other nations to go to war.) Other songs sung that evening,

which afterwards had a great vogue, were one beginning "By blue Patapsco's

billowy dash," arranged by us to an air from "Puritani," and shouted lustily,

and "The years glide slowly by, Lorena," a ditty having a queer quavering

triplet in the heroine's name that served as a pitiful to the unwary singer.

"Stonewall Jackson's Way" came on the scene afterwards, later in the war.Another

incident of note, in personal experience during the autumn of '61, was

that to two of my cousins and to me was intrusted the making of the first

three battle-flags of the Confederacy, directly after Congress had decided

upon a design for them. They were jaunty squares of scarlet crossed with

dark blue, the cross bearing stars to indicate the number of the seceding

States. We set our best stitches upon them, edged them with golden fringes,

and when they were finished dispatched one to Johnston, another to Beauregard,

and the third to Earl Van Dorn, - the latter afterwards a dashing calvary

leader, but then commanding infantry at Manassas. The banners were received

with all the enthusiasm we could have hoped for; were toasted, feted, cheered

abundantly. After two years, when Van Dorn had been killed in Tennessee,

mine came back to me, tattered and smoke-stained from long and honorable

service in the field. But it was only a little while after it had been

bestowed that there arrived one day at our lodgings in Culpeper a huge,

bashful Mississippi soul, - one of the most daring in the army, - with

the frame of a Hercules and the face of a child He was bidden to

come there by his general, he said, to ask if I would not give him an order

to fetch some cherished object from my dear old home - something that would

prove to me "how much they thought of the maker of that flag!" After some

hesitation I acquiesced, although thinking it a jest. A week later I was

the astonished recipient of a lamented bit of finery left "within the lines,"

a wrap of white and azure, brought to us by Dill himself, with a beaming

face. He had gone through the Union pickets mounted on a load of fire-wood,

and while peddling poultry had presented himself at our town house, whence

he carried off his prize in triumph, with a letter in its folds telling

us how relatives left behind longed to be sharing the joys and sorrows

of those at large in the Confederacy.

Richmond -

The first winter of the

war was spent by our family in Richmond, where we found lodgings in a dismal

rookery familiarly dubbed by its new occupants "The Castle of Ortanto."

It was the old-time Clifton Hotel, honeycombed by subterranean passages,

and crowded to its limits by refugees like ourselves from country homes

within or near the enemy's lines - or "'fugees," as we were all called.

For want of any common sitting-room, we took possession of what had been

a doctor's office, a few steps distant down the hilly street, fitting it

up to the best of our ability; and there we received our friends, passing

many merry hours. In rainy weather we reached it by an underground passageway

from the hotel, an alley through the catacombs; and many a dignitary of

camp or state will recall those "Clifton" evenings. Already the pinch of

war was felt in the commissariat; and we had recourse occasionally to a

contribution supper, or "Dutch treat," when the guests brought brandied

peaches, boxes of sardines, French prunes, and bags of biscuit, when the

hosts contributed only a roast turkey or a ham, with knives and forks.

Democratic feasts those were, where major-generals and "high privates"

met on an equal footing. The hospitable old town was crowded with the families

of officers and members of the Government. One house was made to do the

work of several, many of the wealthy citizens generously giving up their

superfluous space to receive the new-comers. The only public event of notes

was the inauguration of Mr. Davis as President of the "Permanent Government"

of the Confederate States, which we viewed, by the courtesy of Mr. John

R. Thompson, the State Librarian, from one of the windows of the Capitol,

where, while waiting for the exercises to begin, we read "Harper's Weekly"

and other Northern papers, the latest per underground express. That 22nd

of February was a day of pouring rain, and the concourse of umbrellas in

the square beneath us had the effect of an immense mushroom-bed. As the

bishop and the President-elect came upon the stand, there was an almost

painful hush in the crowd. All seemed to feel the gravity of the trust

our chosen leader was assuming. When he kissed the Book a shout when up;

but there was no elation visible as the people slowly dispersed. And it

was thought ominous afterwards, when the story was repeated, that, as Mrs.

Davis, who had a Virginia Negro for coachman, was driven to the inauguration,

she observed the carriage went at a snail's pace and was escorted by four

Negro men in black clothes, wearing white cotton gloves and walking solemnly,

tow on either side of the equipage; she asked the coachman what such a

spectacle could mean, and was answered, "Well, ma'am, you tole me to arrange

everything as it should be; and this is the way we do in Richmon' at funerals

and sich-like." Mrs. Davis promptly ordered the outwalkers away, and with

them departed all the pomp and circumstance the occasion admitted of. In

the mind of a Negro, everything of dignified ceremonial is always associated

with a funeral!

Martial Law -

About March 1st martial

law was proclaimed in Richmond, and a fresh influx of refugees from Norfolk

claimed shelter there. When the spring opened, as the spring does open

in Richmond, with a sudden glory of green leaves, magnolia blooms, and

flowers among the grass, our spirits rose after the depression of the latter

months. If only to shake off the atmosphere of doubts and fears engendered

by the long winter of disaster and uncertainty, the coming activity of

arms was welcome! Personally speaking, there was vast improvement in our

situation, since we had been fortunate enough to find a real home in a

pleasant brown-walled house on Franklin street, divided from the pavement

by a garden full of continuous greenery, where it was easy to forget the

discomforts of our previous mode of life. I shall not attempt to describe

the rapidity with which thrilling excitements succeeded each other in our

experiences in this house. The gathering of many troops around the town

filled the streets with a continually moving panorama of war, and we spent

our time in greeting, cheering, choking with sudden emotion, and quivering

in anticipation of what was yet to follow. We had now finished other battle-flags

begun by way of patriotic handiwork, and one of them was bestowed upon

the "Washington Artillery" of New Orleans, a body of admirable daughters

of Virginia in proportion, I dare say, to the woe they had created among

the daughters of Louisiana in bidding them goodbye. One morning an orderly

arrived to request that the ladies would be out upon the veranda at a given

hour; and punctual to the time fixed, the travel-stained battalion filed

past our house. These were no holiday soldiers. Their gold was tarnished

and their scarlet faded by son and wind and gallant service - they were

veterans now on their way to the front, where the call of duty never failed

to find the flower of Louisiana. As they came in line with us, the officers

saluted with their swords, the band struck up "My Maryland," the tired

soldiers sitting upon the caissons that dragged heavily through the muddy

street set up a rousing cheer. And there in the midst of them, taking the

April wind with daring color, was our flag, dipping low until it passed

us.

Well! one must grow old

and cold indeed before such things are forgotten.

A few days later, on coming

out of church - it is a curious fact that most of our exciting news spread

over Richmond on Sunday, and just at that hour - we heard of the crushing

blow of the fall of New Orleans and the destruction of the ironclads; my

brother had just reported aboard one of those splendid ships, as yet unfinished.

As the news came directly from our kinsman, General Randolph, the Secretary

of War, there was no doubting it; and while the rest of us broke into lamentation,

Mr. Jules De St. Martin, the brother-in-law of Mr. Benjamin, mearly shrugged

his shoulders, with a thoroughly characteristic gesture, making no remark.

"This must affect your

interests," some one said to him inquiringly.

"I am ruined, voila

tout!" was the rejoinder - a fact too soon confirmed.

This debonair little gentleman

was one of the greatest favorites of our war society in Richmond. His cheerfulness,

his wit, his exquisite courtesy, made him friends everywhere; and although

his nicety of dress, after the pattern of the boulevardier fini of

Paris, was the subject of much wonderment to the populace when he first

appeared upon the streets, it did not prevent him from going promptly to

join the volunteers before Richmond when occasion called, and roughing

it in the trenches like a veteran. His cheerful endurance of hardship during

a freezing winter of camp life became a proverb in the army later in the

siege.

New Orleans and the Mississippi

River -

For a time nothing was

talked of by the capture of New Orleans. Of the midshipman brother we heard

that on the day previous to the taking of the forts, after several days'

bombardment, by the United States fleet under Flag-Officer Farragut, he

had been sent in charge of ordnance and deserters to a Confederate vessel

in the river; that Lieutenant R____, a friend of his, on the way to report

at Fort Jackson during the hot shelling, had invited the lad to accompany

him by way of a pleasure trip; that while they were crossing the moat around

Fort Jackson, in a canoe, and under heavy fire, a thirteen-inch mortar-shell

had struck the water near, half filing their craft; and that, after watching

the fire from this point for an hour, C_____ had pulled back again alone,

against the Mississippi current, under fire for a mile and a half of the

way - passing an astonished alligator who had been hit on the head by a

piece of shell and was dying under protest. Thus ended a trip alluded to

by C____ twenty years later as an example of juvenile foolhardiness, soundly

deserving punishment.

Aboard the steamship Star

of the West, next day, he and other midshipmen in charge of millions

of gold and silver coin from the mint and banks of New Orleans, and millions

more of paper money, over which they were ordered to keep guard with drawn

swords, hurried away from the doomed city, where the enemy's arrival was

momentarily expected, and where the burning ships and steamers and bales

of cotton along the levee made a huge crescent of fire. Keeping just ahead

of the enemy's fleet, they reached Vicksburg, and thence went overland

to Mobile, where their charge was given up in safety.

Chickahominy and the Seven Pines -

And now we come to the

31st of May, 1862, when the eyes of the whole continent turned to Richmond.

On that day Johnston assaulted the portion of McClellan's troops which

had been advanced to the south side of the Chickahominy, and had there

been cut off from the main body of the army by the sudden rise of the river,

occasioned by a tremendous thunder-storm. In face of recent reverses, we

in Richmond had begun to feel like the prisoner of the Inquisition in Poe's

story, cast into a dungeon with slowly contracting walls. With the

sound of guns, therefore, in the direction of Seven Pines, every heart

leaped as if deliverance were at hand. And yet there was no joy in the

wild pulsation, since those to whom we looked for succor were our own flesh

and blood, standing shoulder to shoulder to bar the way to a foe of superior

numbers, abundantly provided as we were not with all the equipment's of

modern warfare, and backed by a mighty nation as determined as ourselves

to win. Hardly a family in the town whose father, son, or brother was not

part and parcel of the defending army.

Frayser's Farm-House, From

the Quaker or Church Road, Looking South.

From Photograph by E.

S. Anderson, 1885

When on the afternoon

of the 31st it became known that the engagement had begun, the women of

Richmond were still going about their daily vocations quietly, giving no

sign of the inward anguish of apprehension. There was enough to do now

in preparation for the wounded; yet, as events proved, all that was done

was not enough by half. Night brought a lull in the cannonading. People

lay down dressed upon their beds, but not to sleep, while their weary soldiers

slept upon their arms. Early next morning the whole town was on the street.

Ambulances, litters, carts, every vehicle that the city could produce,

went and came with a ghastly burden; those who could walk limped painfully

home, in some cases so black with gunpowder they passed unrecognized. Women

with pallid faces flitted bareheaded through the streets, searching for

their dead or wounded. The churches were thrown open, many people visiting

them for a sad communion-service or brief time of prayer; the lecture-rooms

of various places of worship were crowded with ladies volunteering to sew,

as fast as fingers and machines could fly, the rough beds called for by

the surgeons. Men too old or infirm to fight went on horseback or afoot

to meet the returning ambulances, and in some cases served as escort to

their own dying sons. By afternoon of the day following the battle, the

streets were one vast hospital. To find shelter for the suffers a number

of unused buildings were thrown open. I remember, especially, the St. Charles

Hotel, a gloomy place, where two young girls went to look for a member

of their family, reported wounded. We had tramped in vain over pavements

burning with the intensity of the sun, from one scene of horror to another,

until our feet and brains alike seemed about to serve us no further. The

cool of those vast dreary rooms of the St. Charles was refreshing; but

such a spectacle! Men in every stage of mutilation lying on the bare boards

with perhaps a haversack or an army blanket beneath their heads, - some

dying, all suffering keenly, while waiting their turn to be attended to.

To be there empty-handed and impotent nearly broke our hearts. We passed

from one to the other, making such slight additions to their comfort as

were possible, while looking in every upturned face in dread to find the

object of our search. This sorrow, I may add, was spared the youth arriving

at home later with a slight flesh-wound. The condition of things at this

and other improvised hospitals was improved next day by the offerings from

many churches of pew-cushions, which sewn together, served as comfortable

beds; and for the remainder of the war their owners thanked God upon bare

benches for every "misery missed" that was "mercy gained." To supply food

for the hospitals the contents of larders all over town were emptied into

baskets; while cellars long sealed and cobwebbed, belonging to the old

Virginia gentry who knew good Port and Madeira, were opened by the Ithuriel's

spear of universal sympathy. There was not much going to bed that night,

either; and I remember spending the greater part of it leaning from my

window to seek the cool night air, while wondering as to the fate of those

near to me. There was a summons to my mother about midnight. Two soldiers

came to tell her of the

The Rear Of The Column

wounding of one close

of kin; but she was already on duty elsewhere, tireless and watchful as

ever. Up to that time the younger girls had been regarded as superfluities

in hospital service; but on Monday two of us found a couple of rooms where

fifteen wounded men lay upon pallets around the floor, and, on offering

our services to the surgeons in charge, were proud to have them accepted

and to be installed as responsible nurses, under direction of an older

and more experienced woman. The constant activity our work entailed was

a relief from the strained excitement of life after the battle of Seven

Pines. When the first flurry of distress was over, the residents of those

pretty houses standing back in gardens full of roses set their cooks to

work, or better still, went themselves into the kitchen, to compound delicious

messes for the wounded, after the appetizing old Virginia recipes. Flitting

about the streets in the direction of the hospitals were smiling white-jacketed

Negroes, carrying silver trays with dishes of fine porcelain under napkins

of thick white damask, containing soups, creams, jellies, thin biscuit,

eggs a' la creme, broiled chicken, etc., surmounted by clusters of freshly

gathered flowers. A year later we had cause to pain after these culinary

glories, when it came to measuring out, with sinking hearts, the meager

portions of milk and food we could afford to give our charges.

As an instance, however,

that quality in food was not always appreciated by the patients, my mother

urged upon one of her suffers (a gaunt and soft-voiced Carolinian from

the "piney-woods district") a delicately served trifle from some neighboring

kitchen.

"Jes ez you say, old miss,"

was the weary answer, "I ain't a-contradictin' you. It mout be good for

me, but my stomick's kinder sot again it. There ain't but one thing I'm

sorta yarnin' arter, an' that's a dish o' greens en bacon fat, with a few

molarses poured onto it."

From our patients, when

they could syllable the tale, we had accounts of the fury of the fight,

which were made none the less horrible by such assistance as imagination

could give to the facts. I remember that they told us of shot thrown

from the enemy's batteries into the advancing ranks of the Confederates,

that plowed their way through lines of flesh and blood before exploding

in showers of musket-balls to do still further havoc. Before these awful

missiles, it was said, our men had fallen in swaths, the living closing

over them to press forward in the charge.

It was at the end of one

of these narration's that a piping voice came from a pallet in the corner:

"They fit right smart, them Yanks did, I tell you!" and not to laugh

was as much of an effort as it had just been not to cry.

From one scene of death

and suffering to another we passed during those days of June. Under

a withering heat that made the hours preceding dawn the only ones of the

twenty-four endurable in point of temperature, and a shower bath the only

form of diversion we had time or thought to indulge in, to go out-of-doors

was sometimes worse than remaining in our wards. But one night, after several

of us had been walking about town in a state of panting exhaustion, palm-leaf

fans in hand, a friend persuaded us to ascend to the small platform on

the summit of the Capitol, in search of fresher air. To reach it was like

going through a vapor-bath, but an hour amid the cool breezes above the

tree-tops of the square was a thing of joy unspeakable.

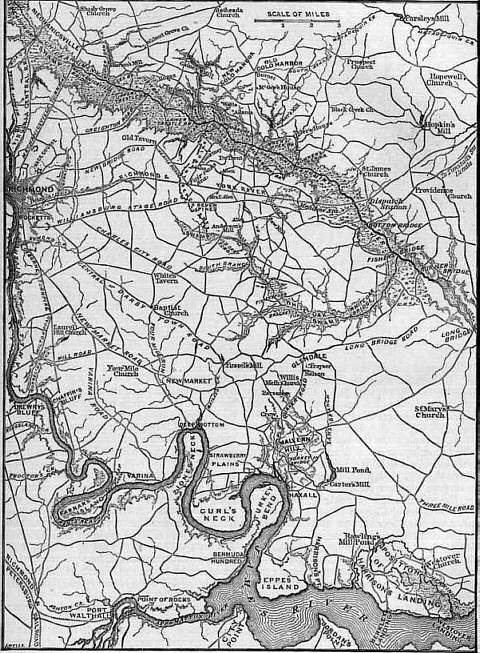

Region Of The Seven Days'

Fighting

Day by day we were called

to our windows by the wailing dirge of a military band preceding a soldier's

funeral. One could not number those sad pageants; the coffin crowned with

cap and sword and gloves, the riderless horse following with empty boots

fixed in the stirrups of an army saddle; such soldiers as cold be spared

from the front marching after with arms reversed and crape-enfolded banners;

the passers-by standing with bare, bent heads. Funerals less honored outwardly

were continually occurring. Then and thereafter the green hillsides of

lovely Hollywood were frequently upturned to find resting-places for the

heroic dead. So much taxed for time and attendants were the funeral officials,

it was not unusual to perform the last rites for the departed at night.

A solemn scene was that in the July moonlight, when, with the few who valued

him most gathered around the grave, we laid to rest one of my own nearest

kinsmen, about whom in the old service of the United States, as in that

of the Confederacy, it was said, "He was a spotless knight."

Around Richmond -

Spite of its melancholy

uses, there was no more favorite walk in Richmond than Hollywood, a picturesquely

beautiful spot, where high hills sink into velvet undulations, profusely

shaded with holly, pin, and cedar, as well as by trees of deciduous foliage.

In spring the banks of the stream that runs through the valley were enameled

with wild flowers, and the thickets were full of May-blossom and dogwood.

Mounting to the summit of the bluff, one may sit under the shade of some

ample oak, to view the spires and roofs of the town, with the white colonnade

of the distant Capitol. Richmond, those seen beneath her verdant foliage

"upon hills, girdled by hills," confirms what an old writer felt called

to exclaim about it, "Verily this city hath a pleasant seat." On the right,

below this point, flows the rushing yellow river , making ceaseless turmoil

around islets of rock whose rifts are full of birch and willow, or leaping

impetuously over the bowlders [sic] of granite that strew its bed. Old-time

Richmond folk used to say that the sound of their favorite James (or "jeems,"

to be exact) went with them into foreign countries, during no matter how

many years of absence, haunting them like a strain of sweetest music; nor

would they permit a suggestion of superiority in the flavor of any other

fluid to that of a draught of its amber waters. So blent with my own memories

of war is the voice of that tireless river, that I seem to hear it yet,

over the tramp of rusty battalions, the short imperious stroke of the alarm-bell,

the clash of passing bands, the gallop of eager horsemen, the roar of battle

or of flames leaping to devour their prey, the moan of hospitals, the stifled

note of sorrow!

President Jefferson Davis -

During all his time President

Davis was a familiar and picturesque figure on the streets, walking through

the Capitol square from his residence to the executive office in the morning,

not to return until late in the afternoon, or riding just before nightfall

to visit one or another of the encampments near the city. He was tall,

erect, slender, and of a dignified and soldierly bearing, with clear-cut

and high-bred features, and of a demeanor of stately courtesy to all. He

was clad always in Confederate gay cloth, and wore a soft felt hat with

wide brim. Afoot, his step was brisk and firm; in the saddle he rode admirably

and with a martial aspect. His early life had been spent in the Military

Academy at West Point and upon the then north-western frontier in the Black

Hawk War, and he afterwards greatly distinguished himself at Monterey and

Buena Vista in Mexico; at the time when we knew him, everything in his

appearance and manner was suggestive of such a training. He was reported

to feel quite out of place in the office of President, with executive and

administrative duties, in the midst of such a war; General Lee always spoke

of him as the best of military advisers; his own inclination was to be

with the army, and at the first tidings of sound of a gun, anywhere within

reach of Richmond, he was in the saddle and off for the spot - to the dismay

of his staff-officers, who were expected to act as an escort on such occasions,

and who never knew at what hour of the night or of the next day they should

get back to a bed or a meal. The stories we were told of his adventures

on such excursions were many, and sometimes amusing. For instance,

when General Lee had crossed the Chickahominy, to commence the Seven Days'

battles, President Davis, with several staff-officers, overtook the column,

and, accompanied by the Secretary of War and a few other non-combatants,

forded the river just as the battle in the peach orchard at Mechanicsville

began. General Lee, surrounded by members of his own staff and other officers,

was found a few hundred yards north of the bridge, in the middle of the

broad road, mounted and busily engaged in directing the attack then about

to be made by a brigade sweeping in line over the fields to the east of

the road and towards Ellerson's Mill, wherein a few minutes a hot engagement

commenced. Shot, from the enemy's guns out of sight, went whizzing overhead

in quick succession, striking every moment nearer the group of horsemen

in the road, as the gunners improved their range. General Lee observed

the President's approach, and was evidently annoyed at what he considered

a fool-hardy expedition of needless exposure of the head of the Government,

whose duties were elsewhere. He turned his back for a moment, until Col.

Chilton had been dispatched at a gallop with the last direction to the

commander of the attacking brigade; then, facing the cavalcade and looking

like the god of war indignant, he exchanged with the President a salute,

with the most frigid reserve of anything like welcome or cordiality. In

an instant, and without allowance of opportunity for a word from the President,

the general, looking not at him but at the assemblage at large, asked in

a tone of irritation:

"Who are all this army

of people, and what are they doing here?"

No one moved or spoke,

but all eyes were upon the President - everybody perfectly understanding

that this was only an order for him to retire to a place of safety; and

the roar of the guns, the rattling fire of musketry, and the bustle of

a battle in progress, with troops continually arriving across the bridge

to go into action, went on. The President twisted in his saddle, quite

taken aback at such a greeting - the general regarding him now with glances

of growing severity. After a painful pause the President said, with a voice

of deprecation:

"It is not my army, general."

"It certainly is not my

army, Mr. President," was the prompt reply, "and this is no place for it"

- in an accent of command unmistakable. Such a rebuff was a stunner to

the recipient of it, who soon regained his own serenity, however, and answered:

"Well, general, if I withdraw,

perhaps they will follow," and, raising his hat in another cold salute,

he turned is horse's head to ride slowly towards the bridge - seeing, as

he turned, a man killed immediately before him by a shot from a gun which

at that moment go the range of the road. The President's own staff-officers

followed him, as did various others; but he presently drew rein in the

stream, where the high bank and the bushes concealed him from General Lee's

repelling observation, and there remained while the battle raged. The Secretary

of War had also made a show of withdrawing, but improved the opportunity

afforded by rather a deep ditch n the roadside to attempt to conceal himself

and his horse there for a time from General Lee, who at that moment was

more to be dreaded that the enemy's guns.

Seven Days' Battle and

Aftermath -

When on the 27th of June

the Seven Days' strife began, there was none of the excitement attending

the battle of Seven Pines. People had shaken themselves down, as it were,

to the grim reality of a fight that must be fought. "Let the war bleed,

and let the mighty fall," was the spirit of their cry.

It is not my purpose to

deal with the history of those awful Seven Days. Mine only to speak

of the rear side of the canvas where heroes of two armies passed and repassed

as if upon some huge Homeric frieze, in the maneuvers of a strife that

hung our land in mourning. The scars of war are healed when this is written,

and the vast "pity of it" fills the heart that wakes the retrospect.

What I have said of Richmond

before these battles will suffice for a picture of the summer's experience.

When the tide of battle receded, what wrecked hopes it left to tell the

tale of the Battle Summer! Victory was ours, but in how many homes was

heard the voice of lamentation to drown the shouts of triumph! Many families,

rich and pour alike, were bereaved of their dearest; and for many of the

dead there was mourning by all the town. No incident of the war, for instance,

made a deeper impressions that the fall in battle of Colonel Munford's

beautiful and brave young son Ellis, whose body, laid across his own caisson,

was carried that summer to his father's house at nightfall, where the family,

unconscious of their loss, were sitting in cheerful talk around the portal.

Another son of Richmond whose death was keenly felt by everybody received

his mortal wound while leading the first charge to break the enemy's line

at Gaines's Mill. This was Lieutenant-Colonel Bradfute Warwick, a young

hero who had won his spurs in service with Garibaldi. Losses like these

are irreparable in any community; and so, with lamentation in nearly every

household. while the spirit along the lines continued unabated, it was

a chastened "Thank God" that went up from among us when Jackson's victory

over Pope had raised the siege of Richmond.

- C. C. Harrison